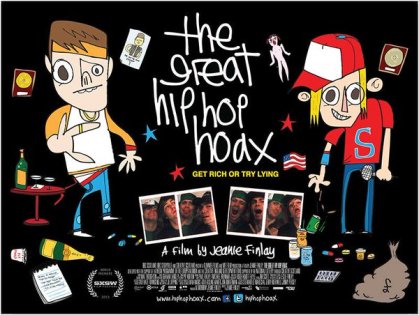

Director: Jeanie Finlay (2013)

The Great Hip Hop Hoax follows a rap duo from Dundee in Scotland who fabricate an elaborate story to secure a record deal. Following a humiliating audition in London where the pair are laughed at by a panel of judges for being Scottish rappers, they become more determined to make their dream come true. Billy Boyd and Gavin Bain reinvent themselves as brash and outlandish Silibil N’ Brains, who hail from California. As soon as the rappers fake American accents their fortunes turn. Booking agents, promoters and even music executives are soon duped by the pretence. Quickly touted as the ‘next big thing’, they land a contract with Sony, but the audacious masquerade and constant fear of being exposed as frauds takes its toll on the rappers. The film documents the astonishing true story of the duo’s rise to fame, their downfall, and the personal toll of the deception.

The film is made up of confessional interviews with the two rappers, as well as music industry personnel, close loved ones who were in on the hoax and others implicated in their web of lies. Intermingled with the unfolding narrative is shaky amateur footage shot by the rappers themselves, which captures the outlandish exploits of the pair following their first advance from Sony. In addition, stylised animation is deployed as a visual means to reconstruct the past. The animation also captures the two-dimensional nature of their rap characters.

At the heart of the story is the contentious issue of authenticity. To be taken seriously, the rappers feel the need to pretend they are from where the culture originates, the USA. Although substantial research on hip hop to date has emerged from the USA, there has been a shift in the last decade recognising hip hop as a global music. Tony Mitchell’s edited book Global Noise: Rap and Hip Hop Outside the USA (2001) arguably signalled the emergence of a body of scholarly work on rap, known as global hip hop studies (Alim et al., 2009). Since then, studies of localised hip hop scenes have been carried out all over the world recognising and celebrating the culture as a meaningful medium of expression and affiliation for youth. However, in the case of the music industry, it seems rap is only authentic if it is American and based on conventional, almost stereotypical, tropes of hip hop. As Gavin states in the film, “It has nothing to do with how good you are. If you want to get on a label, you have to be marketable.” Herein lies the tension between what is deemed ‘authentic’ and what ‘sells’.

For a music that holds ‘being true to oneself’ (Harkness, 2012) as a fundamental tenet of “keepin’ it real”, rappers who fabricate personas and live a lie portraying themselves as American, might immediately seem inauthentic. However, the documentary conveys the complex and often paradoxical nature of authenticity. If these two Scottish rappers wanted nothing more than to be hip hop stars, then perhaps we can understand them as ‘being true’ to that ideal. The contested and messy way in which authenticity can be interpreted and practised is what makes it such a highly charged issue in hip hop (Pennycook, 1997).

The essentialist debate of whether rappers are only considered authentic if they are from where the culture originates and fit the characteristics of the ‘original’ participants i.e. black, working-class and urban (Harkness, 2012) is not just limited to hip hop. There are similar debates in other genres, for instance country music (Peterson, 1997), blues (Grazian, 2003), punk (Williams, 2006) and dance music (Thornton, 1995). Furthermore, as the world becomes increasingly globalised and governed by capitalism, different music and cultural forms will continue to be appropriated and adopted in unlikely places across the globe, making questions of authenticity ever more salient.

Aside from the complicated questions raised about identity and authenticity, the story is also about friendship. Rather than experiencing a sense of condemnation or disapproval towards the main protagonists, the viewer feels sympathy for the young pair who were prepared to go to any length to reach their dreams, ultimately costing them their friendship. The interviews with Gavin Bain and Billy Boyd featured in the documentary had to be shot separately as they were not on speaking terms. The film is thus not just an entertaining account of rappers taking on the British music industry but a moving morality tale about friendship too.

The documentary will not solely be of interest to hip hop fans, but also to audiences interested in popular music or the music industry as the film provides a provocative insight into the way in which the artist-management system functions. Artists have a better chance of success with a well-known manager; though quite often have to relinquish rights to the label, perhaps unwittingly precipitating their downfall. The documentary will also appeal to scholars of authenticity because of the questions it raises concerning what constitutes the ‘real’ and ‘fake’, and the role of commercialisation in music.

The actual deception took place in 2004 leaving the inevitable question at the end of the film that if, ten years on, the pair would be able to ‘make it’ as Scottish rappers today. Although we are now living in a different cultural landscape, which celebrates hybridised and localised manifestations of hip hop, the documentary highlights the crippling power of the music 3 industry. As long as it continues to exercise a controlling influence, in effect the music industry functions as the gatekeeper of authenticity.

Works Cited

Alim, H., Ibrahim, A., Pennycook, A. (eds.) (2009). Global Linguistic Flows: Hip Hop Cultures, Youth Identities, and the Politics of Language. London & New York: Routledge.

Grazian, D. (2003). Blue Chicago: The Search for Authenticity in Urban Blues Clubs. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Harkness, R. (2012). True School: Situational Authenticity in Chicago’s Hip Hop Underground. Cultural Sociology. 6(3) 283-298.

Mitchell, T. (2001). Global Noise: Rap and Hip-hop Outside the USA. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press.

Pennycook, A. (2007). Language, Localization, and the Real: Hip-Hop and the Global Spread of Authenticity. Journal of Language, Identity & Education 6(2) 101-115.

Peterson, R. A. (1997). Creating Country Music: Fabricating Authenticity. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Williams, J. (2006). Authentic Identities: Straightedge Subculture, Music and the Internet. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 25(2) 173-200.

Thorton, S. (1996). Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital. Hanover: University Press of New England.